Oh no, I have to add those stupid TypeScript types

7 min read ·

TypeScript is only becoming more popular. More people want to learn it, and more projects start in TypeScript. Many people decide to use it over JavaScript. However, the problem is how we’re using it.

Most of us come to TypeScript from JavaScript. For some, static typing is something new. Thus TypeScript seems like a completely new language to learn. That’s fair. There are a few things to pick up. It takes some time before one is confident with writing TypeScript, and plain JavaScript may seem far more comfortable. But… they said we can write JavaScript in TypeScript, isn’t that right? Yes, it is! However, it may lead to a kind of a trap. The trap being this thinking: “so I need to write JavaScript, and then FIX my code by adding types”.

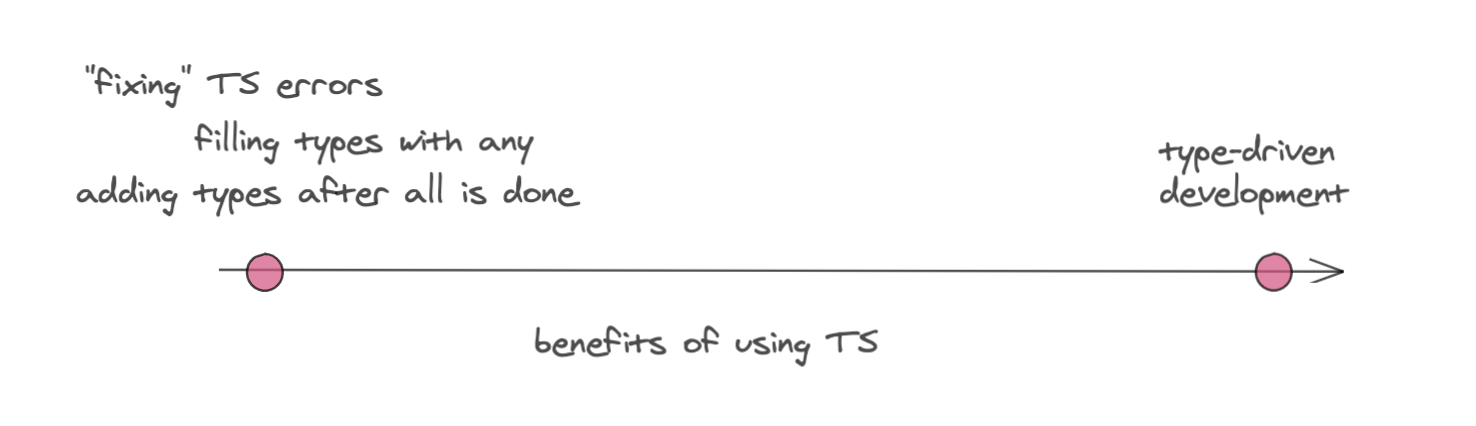

There is a broad spectrum of what TypeScript can give you. On the one side of this spectrum, we have the above thing: writing good old JavaScript, without types or filling the gaps with any, and after the implementation is done — fixing the types. On the other side of the spectrum, we have type-driven development.

With this article, I do not want to preach that type-driven development is superior and the only way to go about writing code. I want to show you that being on the “fixing typescript” side of the spectrum won’t allow you to get the most out of TypeScript and that you may want to go a bit more to the other side.

But let’s make one thing clear — even if you write your code in JS, without types (or annotating everything as any), and then add more types, it’s not like TypeScript is useless. It’s not like you won’t have any (heh) TypeScript benefits. It will still allow you to maintain your code easier, make refactorings faster, prevent you from some embarrassing errors in your client’s browser. However, there’s more to TypeScript. And do we want to settle for less?

So what’s wrong with fixing your code by adding types to a previously written JavaScript code?

You don’t narrow types

The implementation is done, you did a demo for your team, your project manager thinks you can move on to another task. There’s not much time to add types. There’s definitely not enough time to analyze every function, every variable, and add proper, narrow types. Even if something seems obvious or straightforward, it is easy to miss it, especially under pressure.

Example:

ts

ts

This could be format: "JSON" | "CSV", right? However string does work, and maybe the function was huge and there was no time to go through the implementation to get the proper type? I bet it’d be less likely to happen if types were added before or during or even right after implementing the download function when the idea of what this function does is still in your head.

Another example:

ts

ts

res can have error or data, and both fields can be falsy. Quick solution:

Does it work? It does. Can we do better? Yes! We had more information about the res shape (that we forgot when adding types days later). We know that it can be either an object with data property or an object with an error string. So we could include this knowledge in the type:

Note: {data: number} | {error: string} would also work, but in this case, we’d need to narrow the type by using in operator: if ('error' in res) {...}.

You settle for any

Highly dynamic code. Mutability. Complex shapes of objects. Who has the patience to annotate all of it? We could say any and call it a day. Tempting, right? Now imagine sitting down to implement a function. There’s no code yet. You’re about to write a type signature of a function. Would you be like shit, in a few hours this will be a super complex function, so I better annotate everything as any? I bet not. Even if you’re about to write a complex function (and let’s say it’s by design), you would come up with something better than any. The idea of the function is fresh in your head, you know what kind of data will flow through it. It’s the best time to add types and make them work for you when implementing the body; not when you’re tired, overwhelmed with the implementation details, and want to move on to another thing.

You won’t spot lousy code soon enough

Undoubtedly, you’re familiar with the notion that if something is hard to test, it will be hard to maintain. It’s the same deal with types. If something is hard to describe in a statically typed language, won’t it be hard to grasp for your colleagues and the future you? TypeScript may help you rule out bad designs faster. When you’re focused on types without being distracted by the implementation, you can consider multiple ideas, multiple ways of typing something that will then influence the implementation. You can get answers to these kind of questions:

- Does one alternative has simpler types than another?

- Does one alternative enable more efficient implementation than another?

Types let you zoom out in a space of all possible programs and choose the best one.

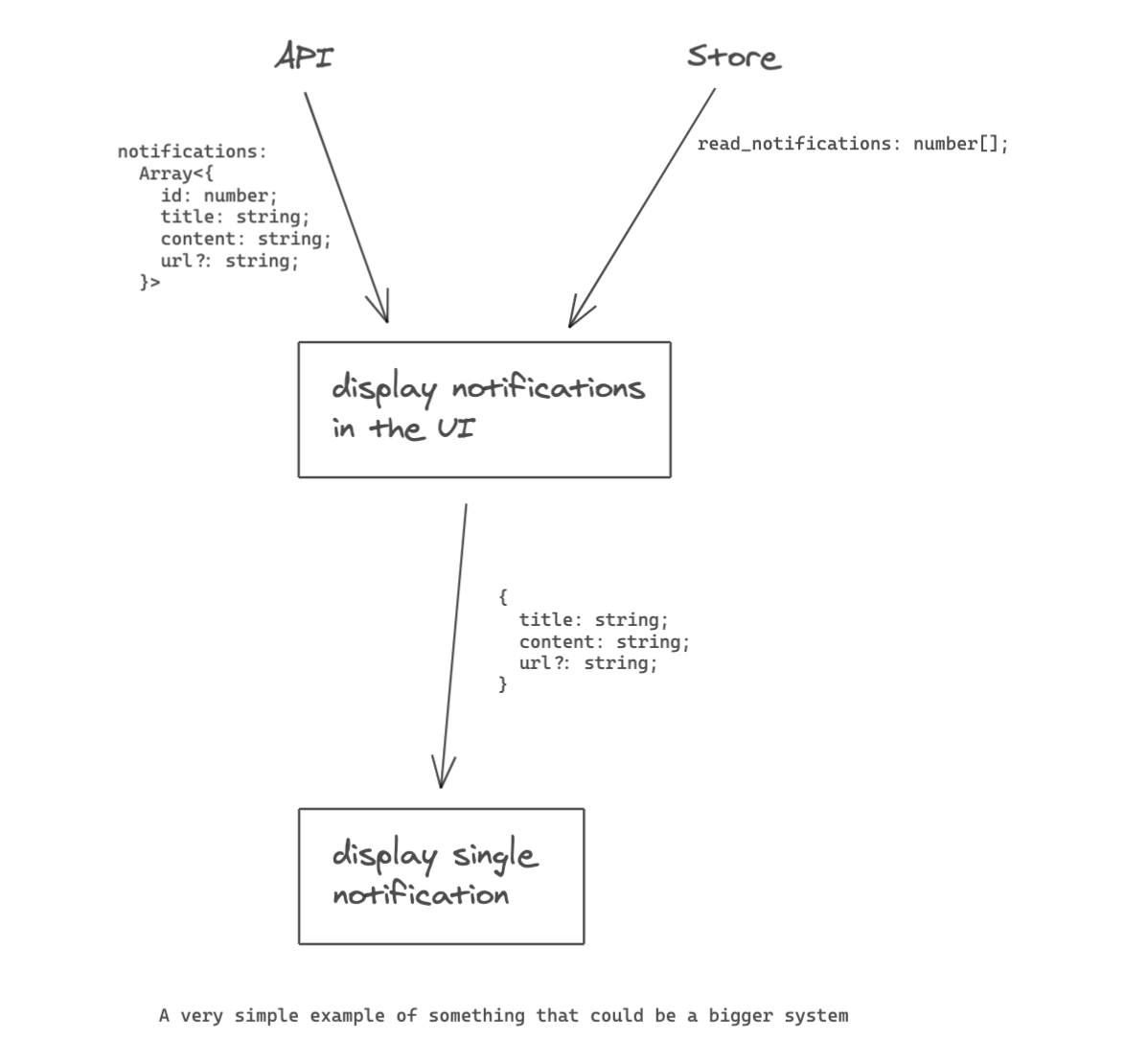

You’re missing out help in coding

Imagine you’re about to implement a bigger feature that requires a few modules, integrating with existing code, and you need to figure out how the data is going to flow through these modules. Working with proper types early can help you see what shapes of data flows through the program, how does it change, what is needed and where. If you don’t yet know how to implement a thing, the code will naturally emerge between those types.

TypeScript is not exactly JavaScript + types

In practice, when you write TypeScript, you’re writing JavaScript, but restricted to the subset that’s conventional in TypeScript, which may differ from the JavaScript you used to.

Despite that TypeScript is a superset of JavaScript, many things that pass in JS will cause a TypeScript compiler error.

An example:

ts

ts

JavaScript will let you write it without any complaints. TypeScript won’t: you’ll see an error Type 'number[]' cannot be used as an index type.(2538). It could be worked around with any or type assertions, but does this implementation even make sense? Shouldn’t we change it before hacking over assumptions that are legal in one language and illegal in another? Would we end up with this code if we added types from the get-go?

You’re less likely to use some TypeScript’s features

For example — union exhaustiveness checking. Usually adding types after writing code is what it is — just adding types. The feature is working, tests are passing, we’re not touching the implementation.

Let’s take this switch statement:

ts

ts

You know that status can be of those four values: loading, request, success, error, and there shouldn’t be any other value. It would be enough to add those types:

ts

ts

It’s working! But hey, every time we add something to Status union, we need to remember about handling it in the getStatus function. Wouldn’t it be better to have TypeScript remembering it for us by using union exhaustiveness checking?

Cool, but how do I actually do this?

It’s all easier said than done, I know. The idea of static typing may be somewhat strange and I get that it takes time to be fairly confident with it. Take small steps and you’ll get more comfortable with TypeScript in no time.

Summary

Static typing makes us think differently. It makes us think more about modelling data, designing APIs, and making things “click together”.

My point with this article is that you can make TypeScript work for you as early as possible. Don’t think about TypeScript as oh no, I have to add those stupid types. Don’t think of it as a fight with compiler errors. Think about types as an integral part of your code. Eventually, writing types and writing runtime code simultaneously will make you change the perspective and write more robust and less complicated code.

Further reading

-

There are many benefits of designing with types. If you want to know more about it, check out the excellent post series on F# for Fun and Profit.

-

If you’re new to TypeScript and want to learn it, check out this amazing tutorial: TypeScript Tutorial for JS Programmers Who Know How to Build a Todo App.